The river crossing at Shushtar | The end of PersiaThe Persian gateAfter crossing the river Pasitigris at a place that can be identified with modern Shushtar, Alexander reached the southern spurs of the Zagros mountains. They are situated between Susiana and the Persian homeland - that is, between modern Khuzestân and the Shîrâz. The Macedonian army would have to force its way through one of the passes. That would be difficult, because the Macedonians were now entering a country where they could not pretend to be liberating the inhabitants. They would encounter resistance from people who were defending their homes and families. | |

The Persian gate: entrance of the valley | Somewhere near Masjid-e Solaiman, Alexander divided his troops, to spread the risks. His trusted general Parmenion was to take a southerly route around the mountains, the Macedonian king would take the main road and would force the Persian gate, which is near modern Yasuj. As could be expected, the satrap of Persis, Ariobarzanes, occupied the pass and Alexander suffered heavy losses when he tried to repeat the frontal attack that had been successful at the Cilician gate. Every pass can be turned and we can be certain that Alexander's scouts searched for a mountain path to get into their enemy's rear. The Greek sources tell a charming story about a shepherd with a grudge against the Persians, who showed them the best way to by-pass the enemy. It may be true, but one suspects that the Greek authors could -before the final punishment of the Persians for the crimes they had committed during Xerxes' campaign- not resist the temptation to invent a traitor. The shepherd may have been introduced as a kind of answer to Ephialtes, who had once showed the Persians the road to the Greek heartland. | |

Persepolis: Gate of all Nations | PersepolisHowever this may be, the Persian garrison in the mountains was destroyed, and in January 330, the Macedonian army stood in Persepolis, the capital of the Achaemenid empire. Many inhabitants fled, some committed suicide, but the governor surrendered the town and its treasure. Alexander gave the town itself to his soldiers, who had seen the riches of the East several times, but had never had their share. So the city was looted, except for the royal palace. Almost at the same time, nearby Pasargadae (Pâthragâda) was captured, Persia's religious capital, where the kings were inaugurated. | |

The Macedonians and Greeks had reached the goal of their crusade: the Persians were punished for the destruction of Athens in 480/479 BCE. But this was not enough for the son of Zeus. He now wanted universal recognition as 'king of Asia'. Alexander had already claimed the title after the battle of Issus, had taken the Persian royal harem (above), had stressed that he descended from Perseus, the legendary ancestor of the Persian kings (above), had been recognized as 'king of the world' in Babylon (above and here), had appointed Persians in important offices (above), and now wanted recognition from all Persians. He needed it, if he were to rule the territories already conquered. Actually, our Greek sources do not mention this explicitly, but it is clear from other evidence. One clue is that Arrian of Nicomedia writes that Alexander intended to visit the tomb of Cyrus the Great after his conquest of Persia (text). This is a way of saying that he wanted to be crowned as king, because this ceremony took place near the tomb. Unfortunately, he could not be enthroned, as long as Darius III Codomannus was still alive. | ||

Another clue is that Alexander stayed at Persepolis for more than four months. This makes no military sense, but a likely explanation is that Alexander wanted to celebrate the New Year festival as if he were Persia's sole ruler. During this festival the Persian nobility came to Persepolis to do homage to the Achaemenid king and Alexander may have seen an opportunity to entice the Iranian aristocracy away from Darius. However, his hopes were disappointed. Except for the Persians he had already appointed in high offices, only a few visitors turned up in the first days of April; one of them was Phrasaortes, who was appointed satrap of Persis. Not having obtained support from the Persian aristocrats, it was war again: the army had to march to Ecbatana (modern Hamadan), the northern capital of the Achaemenid empire, where Darius was. This was the nightmare of the Macedonian high command: to search for an enemy that would certainly move to the eastern part of the Achaemenid empire. Unless Darius stood his ground at Ecbatana, the Macedonian army would be forced to follow him to unknown countries, fighting a war of an unknown type. Eventually, Darius was killed, but Alexander was indeed lured into a disastrous eastern campaign. | ||

Traces of fire on one of the columns of the Apadana ,Persepolis | The sack of PersepolisBefore leaving Persepolis, Alexander ordered the palace to be burnt down. There are two accounts of this incident. First, there is the sober story of the Greek author Arrian of Nicomedia, derived from his source Ptolemy, a close friend of Alexander who was an eyewitness. It states simply that Alexander, after a discussion with his friends, burnt the palace as a retribution for the destruction of Athens. A more romantic account can be found in Plutarch of Chaeronea, Quintus Curtius Rufus and Diodorus of Sicily; these sources are derived from Cleitarchus, who wrote a quarter of a century after the events. He tells that a courtesan named Thais was present at a drinking party and convinced the drunken king that it would be his greatest achievement in Asia to set fire to the palace. At first, this seems to be a cautionary tale for alcoholics without any value as historical source; and we may be inclined to believe Ptolemy's sober statement that the destruction was a premeditated act. However, it can be proven that Ptolemy is not telling the whole truth: Thais was his lover (and the mother of three of his children). It may well be true that she did indeed play a role. | |

Archaeologists have shown that the palace at Persepolis was only partially destroyed and that most buildings received a special treatment from the arsonists. For example, the palace of Xerxes, the destroyer of Athens, was damaged, but that palace of Darius wasn't. Other buildings that were damaged were the Apadana and the Treasury: the symbols of the gift exchange ritual that was the core of the Persian Empire's political system. It is highly unlikely that a fire created randomly by drunken arsonists would destroy exactly these three buildings. The fire was planned (more....). | ||

The desert southeast of modern Isfahan | It remains to find a motive for this vandalism. The Macedonians could not leave the palace behind: the search for Darius promised to be a long and difficult campaign, and it was possible that the Persians would liberate Persepolis and gain access to the remains of the treasury when the Macedonians were at Ecbatana. The destruction of the palace was a military necessity, and the decision to destroy it was made easier because the Persian nobility had not visited the king: they had chosen to be enemies, so they would be treated like enemies. Preparations for the fire-raising must have taken some time and it is possible that they were not completely finished when an intoxicated king decided to commit the 'most detested town in the world' to the flames. | |

| The pursuit of DariusIn May, the Macedonian infantry marched to the northwest, crossing Deh Bid pass, and in June, they reached Ecbatana, the capital of the satrapy Media. But Darius was no longer there. Just a couple of days before, he had gone to the east. It is interesting to note that he had stayed at Ecbatana during the winter, because this proves that he still hoped to be reinforced, could liberate Assyria and Babylonia and cut off the Macedonian lines of supply while Alexander lingered in Persepolis. In fact, during their march to Ecbatana, at Gabae, the Macedonians received word that Darius would indeed receive troops and was prepared to offer battle, but it seems that the new soldiers arrived too late. | |

From now on, Darius III Codomannus was no longer fighting to regain his empire. The great king, the king of kings, the king of Persia, the king of countries, the lord of many kinds of men, the king of all men from the rising to the setting sun, the Persian, an Aryan, the Achaemenid, was now fighting for his survival and hoping to be in Bactria before the Macedonians would overtake him. Even worse, Darius' supporters were wavering. There were divisions within the royal family: a prince named Bisthanes, the son of the former king Artaxerxes III Ochus, surrendered Ecbatana to the Macedonians, the last of Persia's royal capitals to be captured. Alexander continued his policy to lure Persian noblemen away from his opponent: a Persian named Atropates was received an important courtier and later appointed as satrap of Media. He was to become one of the protectors of Zoroastrianism. | ||

King Darius was taking with him the treasure of Ecbatana and traveled slowly. He should have left earlier and he must have cursed the reinforcements that had promised to help him and had caused him to stay at Ecbatana. He reached Rhagae (near modern Tehran), the most important religious center of the Zoroastrians. Darius may have wanted to sacrifice to the sacred fire, but was unable to stop: if Persia and its religion were to have a future, he would have to reach the eastern satrapies and recruit an army. Being killed by the Macedonians was more honorable but would not help the Persians. So he continued to Parthia. | ||

| The death of DariusThe satrap of Bactria was the most important man in the Achaemenid empire after the king. A crown prince would reign Bactria for a couple of years and a king without grown-up sons would appoint his brother in this satrapy. The present governor of Bactria, a man named Bessus, must have been very closely related to Darius and the king must have thought that he was safe when he reached the territory of Bessus. But he was wrong. To Bessus and Barsaentes, the satrap of Arachosia and Drangiana, the situation was clear: if they remained loyal to their king, the Macedonians would invade the eastern satrapies. On the other hand, if they arrested Darius and delivered him to the invaders, there would be no war, because it was unlikely that the Macedonians were interested in unknown countries, where they would be forced to fight a war of an unknown type. But they were wrong too.Alexander and the cavalry followed Darius as fast as they could. After ten or twelve days, the Macedonians were at Rhagae, where they briefly paused; two days later, they crossed the Caspian Gate and reached Parthia, where they met two servants of Darius -one Bagistanes and Artiboles (the son of the satrap of Babylonia, Mazaeus)- who told him that their master had been arrested. The Macedonian king who wanted to be recognized as king of Persia, was now faced with the following choice:

| |

|

| He did not give Bessus a chance to open negotiations, and sent Attalus and Parmenion's son Nicanor ahead to pursue the Persians. At Choara, they reached their enemies, who were struck with terror and killed the captive king (text). This happened in July 330, near modern Dâmghân. The incident is mentioned in the contemporary Babylonian Alexander Chronicle. Darius received a state funeral at Persepolis. Perhaps the "Unfinished tomb" was prepared for him, but this was never completed, and it is more likely that his last resting place was the Tomb of Artaxerxes III. This is interesting, because it proves that Alexander already regretted the destruction of the palace and wanted to do what was expected from a Persian king: restore it. |

http://www.livius.org/aj-al/alexander/alexander10.html

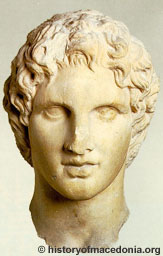

Alexander III the Great, the King of Macedonia and conqueror of the Persian Empire is considered one of the greatest military geniuses of all times. He was inspiration for later conquerors such as Hannibal the Carthaginian, the Romans Pompey and Caesar, and Napoleon. Alexander was born in 356 BC in Pella, the ancient capital of Macedonia. He was son of

Alexander III the Great, the King of Macedonia and conqueror of the Persian Empire is considered one of the greatest military geniuses of all times. He was inspiration for later conquerors such as Hannibal the Carthaginian, the Romans Pompey and Caesar, and Napoleon. Alexander was born in 356 BC in Pella, the ancient capital of Macedonia. He was son of